The Armory Show Was Americas First Exposure to Modern Art True or False

Seeing Isn't Believing: The Arsenal Testify at 100

Seeing Isn't Assertive: The Armory Evidence at 100

In 1913, the Armory Show gave thousands of Americans their first glimpse of modern European painting. At present, in an exhibit entitled The Armory Evidence at 100: Modernism and Revolution, the New York Historical Lodge has made it possible for the states to see what all the excitement was about.

From the publication of D. H. Lawrence'southward Sons and Lovers to the offset staging of Nijinsky's ballet, The Rite of Jump, 1913 was a yr of cultural breakthroughs. In the The states the big breakthrough came with the Armory Show, which gave thousands of Americans their kickoff glimpse of modern European painting.

Now, in an exhibit entitled The Armory Evidence at 100: Modernism and Revolution,the New York Historical Society has made it possible for us to see what all the excitement was nearly a century agone.

The International Exhibit of Mod Art, every bit the Armory Show was officially called when it opened in New York on February 17, 1913, at the 69th Regiment Armory on Lexington Artery, set off a wave excitement that not only changed American fine art merely encouraged Americans to go involved in the art battles of their day. Newspapers turned out editorials and cartoons about the Arsenal Show. Even former president Theodore Roosevelt felt compelled to write nearly his visit.

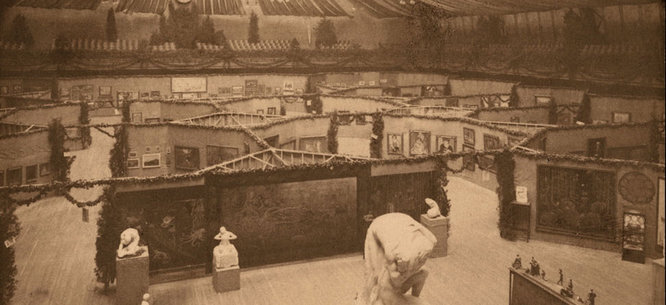

Before the Armory Show closed its month run in New York and traveled to Chicago and Boston, 87,000 people had seen it. Hung in eighteen octagonal spaces, consisting of temporary walls covered in burlap, the evidence was organized by the Association of American Painters and Sculptors.

The Arsenal Evidence at 100, which features over one hundred works from the 1913 show, honors the original vision of the Clan of American Painters and Sculptors, but with a departure. The current exhibit, which continues through February 23, is a lot easier to view than the 1913 exhibit was a century ago in the cavernous 69 th Regiment Arsenal.

The Armory Prove at 100 fills the well-lit, main gallery of the Historical Guild with its 19-pes-high ceilings and iii,000 square feet of infinite and reflects the careful planning of Marilyn Satin Kushner and Kimberly Orcutt of the Historical Society and Casey Blake of Columbia Academy, who served as the prove's senior historian.

American artists are particularly well represented by such Ashcan School realists every bit John Sloan and George Bellows, whose work captures the rise of modern New York. Only it is the European artists, ranging from Cezanne to Picabia, whose work is the real draw. Whether information technology is through their Fauvist use of color or their embrace of Cubism, their paintings are the ones that defy past history. They are the stars of the Armory Bear witness.

Minor wonder that the conservative American art critic Kenyon Cox complained that the Europeans who appeared in the Armory Evidence were bent on bringing about "the full destruction of painting as a representative art." The Europeans were, indeed, all besides happy to abandon the strictures of mimetic art.

Null makes the depth of this European challenge clearer than a series of paintings by Robert Henri, Henri Matisse, and Marcel Duchamp, all of them of nudes, that were central to the original Armory Show and are equally cardinal to the Arsenal Prove at 100.In her essay for the catalog, Kimberly Orcutt, the Historical Society'due south curator of American art, rightly argues that, when viewed together, these paintings plant "a dialogue of nudes" that puts the Armory Bear witness in perspective.

Robert Henri, Figure in Movement, 1913.

The influential American painter Robert Henri's 1913 Figure in Motion is the about conventional of the three paintings, even though Henri has abased the thought of presenting his model in a traditional static pose. His model balances on one foot and gestures with her arm. Henri, who believed that "The but true modern movement is a frank expression of cocky," has lived upwardly to his own philosophy in his portrait. The woman at the middle of his life-size painting, which he completed just weeks before the Arsenal Show opened, is hit, but she is non passively waiting to exist admired. She is in command of her actions, and it is merely natural for the viewer to wonder where she is going to pace next.

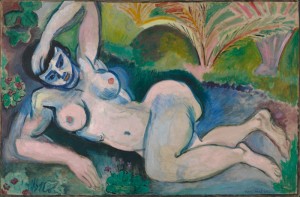

The contrast with Matisse'south Bluish Nude, done 5 years earlier in 1907, could not be more than dramatic. Matisse'southward model reclines earlier the viewer every bit nude of Titian might have done, only in this case the viewer isn't struck by her every bit an private. Her confront and body are sketched in rather than carefully rendered. What makes her arresting is the blueish that Matisse, who had 13 paintings in the Armory Show, employed to outline her figure and shade her skin. It is Matisse's innovative use of colour, rather than his bodily model, that is the subject of his pic.

Henri Matisse, Blue Nude, 1907.

The same gap betwixt art and twenty-four hour period-to-twenty-four hour period reality likewise lies at the heart of the painting that got the most attention in the Armory Evidence, Marcel Duchamp'due south 1912 Nude Descending a Staircase (No. two). Visitors waited in line for up to forty minutes to run across Duchamp'southward Cubist work, simply one time they saw it, they found themselves confounded. The woman in Duchamp painting is not someone we tin point to and say here is her leg, hither is her arm, here is her confront. The American Fine art News was not simply being facetious when information technology offered a $10 prize to anyone who could "discover the lady" in Duchamp's painting.

Marcel Duchamp, Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2), 1912.

In Nude Descending a Staircase, nosotros don't come across a recognizable or an erotic figure. Nosotros encounter instead a serial of overlapping, geometric planes that create the illusion of movement and simultaneously erase any notion that nosotros are looking at a specific person. As with Bluish Nude, the true focus of Duchamp's painting lies in his fascination with the power of the artist to shape perception and create an independent aesthetic.

Today, information technology is clear that in their emphasis on artistic technique that had an contained life of its own, the modernists of the Armory Evidence were not merely breaking with the by. They were anticipating the abstruse expressionism that in the work of Jackson Pollock and his contemporaries would come up to dominate American art in the 1940s and 1950s.

What Cox and those who felt threatened by the Arsenal Show did not foresee in 1913 was that the Armory Show's modernism would non marking the finish of representational fine art in America. Instead, information technology would marker the get-go of a more expansive American art market in which a multifariousness of schools would flourish at the same time. As the work of Edward Hopper, Fairfield Porter, and Neil Welliver shows, American artists who paint in a representational manner have had no trouble since the Armory Testify in finding both collectors and an appreciative museum-going audience.

When we look back on 1913, it is easy to meet why the Armory Evidence ignited such fears, but equally of import, it is easy to envy those who fought so hard to define the meaning of the Arsenal Evidence. They had such rich art to fight over.

Past contrast, our best-known contemporary fine art battles seem trivial. The international controversy that arose in 1989 over Andres Serrano'due south Piss Christ was a battle over a 60 x 40 inch cherry and yellow photograph of a crucifix plunged into a vat of Serrano's urine. The controversy that arose in 1999 over Chris Ofili's Holy Virgin Mary during the Sensation art show at the Brooklyn Museum was a battle over an eight-human foot-tall portrait of the Virgin Mary that contained clumps of elephant dung and cutouts of female genitalia from pornographic magazines.

Victory in these contemporary fine art battles was a victory over censorship, just how trivial of lasting value came with victory.

Nicolaus Mills is professor of American studies at Sarah Lawrence College and author of Winning the Peace: The Marshall Plan and America's Coming of Age equally a Superpower.

Paradigm Credits:

Robert Henri (American, 1865–1929), Figure in Motion, 1913. Oil on canvas. Terra Foundation for American Art, Chicago, Ill., Daniel J. Terra Collection, 1999.69

Henri Matisse (French, 1869-1954), Blue Nude, 1907. Oil on canvas, 36 ¼ 10 55 ¼ in. The Baltimore Museum of Art: The Cone Collection, formed past Dr. Claribel Cone and Miss Etta Cone of Baltimore, Maryland, BMA 1950.228. © 2013 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Lodge (ARS), New York. Photography by Mitro Hood.

Marcel Duchamp (French, 1887-1968), Nude Descending a Staircase (No. ii), 1912. Oil on canvass, 57 seven/8 x 35 1/8 in. Philadelphia Museum of Art, The Louise and Walter Arensberg Collection, 1950, 1950-134-59. © 2013 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris / Succession Marcel Duchamp

foelschethereve35.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.dissentmagazine.org/online_articles/seeing-isnt-believing-the-armory-show-at-100

0 Response to "The Armory Show Was Americas First Exposure to Modern Art True or False"

Post a Comment